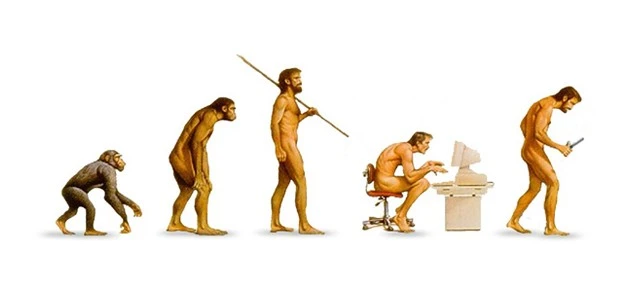

Der menschliche Körper ist für Bewegung gemacht

Viele von uns verbringen einen Großteil des Tages im Sitzen, sei es im Büro, im Auto oder auf dem Sofa. Allerdings kann langes Sitzen negative Auswirkungen auf unsere Gesundheit haben.

Zur Abwehr dieser negativen Effekte ist es von großer Bedeutung, Bewegung in unseren Alltag zu integrieren. Hier sind fünf überzeugende Gründe, warum Bewegung während des Sitzens nicht nur notwendig, sondern sogar gesundheitsfördernd ist:

- Unser Körper ist biologisch auf Bewegung ausgerichtet.

- Ein bewegungsarmer Lebensstil kann unserem Körper erheblichen Schaden zufügen.

- Regelmäßige Bewegung während des Sitzens kann Muskelschwund und Gelenksteifigkeit vorbeugen.

- Bewegung während des Sitzens fördert außerdem die Durchblutung und verbessert den Stoffwechsel.

- Regelmäßige Bewegung im Alltag trägt dazu bei, dass wir gesund und fit bleiben.

Trotz dieser Fakten verbringen die meisten Menschen einen Großteil ihrer Bürozeit sitzend, oft ohne ausreichende Pausen. Daher ist die DUOAir Sitzauflage darauf ausgerichtet, diese Herausforderung zu meistern und Ihre Gesundheit zu unterstützen, indem es Ihnen hilft, auch während des Sitzens in Bewegung zu bleiben. Denn Ihr Wohlbefinden ist unser Anliegen.

Zu lange Sitzen ist wie das Rauchen. Beides ist gleich schädlich.

Häufige Fragen über gesundheitliche Auswirkungen von langem Sitzen

Literaturempfehlungen (Bücher)

Literaturempfehlungen (wissenschaftliche Literatur)

- Aarås, A. H. (2000). Work with the visual display unit: Health consequences. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 12(1), 107-134.

- AUVA. (01 2018). Merkblatt 026 - Sicherheit Kompakt - Bildshirmarbeitsplätze. Von https://www.auva.at/cdscontent/load?contentid=10008.544628 abgerufen

- Bildschirmarbeitsverordnung. (StF: BGBl. II Nr. 124/1998 (CELEX-Nr.: 390L0270) 1998 ). Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Arbeit, Gesundheit und Soziales über den Schutz der Arbeitnehmer/innen bei Bildschirmarbeit (Bildschirmarbeitsverordnung § 5 – BS- V).

- Biswas, A., Oh, P. I., Faulkner, G. E., Bajaj, R. R., Silver, M. A., Mitchell, M. S., & Alter, D. A. (2015). Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine, 162(2).

- Callaghan, J. P. (2002). Examination of the flexion relaxation phenomenon in erector spinae muscles during short duration slumped sitting. Clinical Biomechanics, 17(5), 353-360.

- Center for Disease Control. (1996). Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Center for disease control and prevention. www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/pdf/sgrfull.pdf

- Claus, A. P. (2009a). Is ‘ideal’ sitting posture real?: Measurement of spinal curves in four sitting postures. Manual Therapy, 14, 404-408.

- Daian, I. V. (August 2007). Sensitive chair: a force sensing chair with multimodal real-time feedback via agent. In Proceedings of the 14th European conference on Cognitive ergonomics: invent! explore! , 163-166.

- Ellegast, R. P. (2012). Comparison of four specific dynamic office chairs with a conventional office chair: impact upon muscle activation, physical activity and posture. Applied ergonomics, 43(2), 296-307.

- Gregory, D. E. (2006). Stability Ball Versus Office Chair: Comparison of Muscle Activation and Lumbar Spine Posture During Prolonged Sitting. Human Factors, 48(1), 142-153.

- Groenesteijn, L. V. (2009). Effects of differences in office chair controls, seat and backrest angle design in relation to tasks. Applied ergonomics, 40(3), 362-370.

- Haller M., R. C. (September 2011). Finding the Right Way for Interrupting People Improving Their Sitting Posture. IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 1-17. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Jensen, E. (2000). Moving with the brain in mind. Educational leadership, 58(3).Kelsey, J. L. (1980). Epidemiology and impact of low-back pain. Spine, 5(2), 133-142.

- Levine, J. A. (2014). Get Up!: Why Your Chair is Killing You and what You Can Do about it. Sr. Martin’s Press, New York.

- Li, G. &. (1999). Current techniques for assessing physical exposure to work-related musculoskeletal risks, with emphasis on posture-based methods. Ergonomics, 42(5), 674-695.

- Müller-Lutz, H. L. (1964). Das programmierte Büro. Gabler Verlag.

- O’sullivan, P. B. (2006). Effect of different upright sitting postures on spinal-pelvic curvature and trunk muscle activation in a pain-free population. Spine, 31(19), E707-E712.

- ÖNORM EN 1335-1, Büromöbel, Büro-Arbeitsstuhl, Teil 1: Maße - Bestimmung der Maße. (ÖNORM EN 1335-1, 2000).

- Pynt, J. H. (2001). Seeking the optimal posture of the seated lumbar spine. Physiotherapy theory and practice, 17(1), 5-21.

- Thömmes, F. (2017). Wer länger sitzt, ist früher tot. Das Erste-Hilfe-Programm für Vielsitzer gegen Haltungsschäden und Schmerzen. München: Riva Verlag.

- Veerman, J. L., Healy, G. N., Cobiac, L. J., Vos, T., Winkler, E. A., Owen, N., & Dunstan, D. W. (2011). Television viewing time and reduced life expectancy: a life table analysis. British journal of sports medicine 46.

- WHO. Health topics: Physical Activity, www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- Wottke, D. (2013). Die große orthopädische Rückenschule: Theorie, Praxis, Didaktik. Springer-Verlag.